All About Exercise Intensity: The Pros and Cons of Low, Moderate, and High-Intensity Exercise

This blog post was written by Victoria L. Freeman, Ph.D., CHFS, CMH, CBC.

Any type of exercise – lifting weights, jogging, swimming, cycling, yoga, or even walking — can be performed in a high, moderate, or low-intensity fashion. The difference is how much energy we exert, which equates to intensity. Are you pushing yourself hard (high intensity)? Are you putting forth some effort but haven’t yet reached your upper limit (moderate intensity)? Or are you moving but leaving quite a bit in your tank (low intensity)? Any sort of training is better than none since the general benefits of a consistent exercise program include improvements in cardiovascular health, muscle strength and endurance, bone and connective tissue strength, blood sugar balance, brain health, sleep quality, energy, self-confidence, and self-discipline.2 Given this menu of rewards, the best kind of exercise is the one you’ll stick with over the long haul.

Still, intensity matters. All exercise is not created equal. Higher-intensity training stimulates your body in a different way than moderate or lower-intensity does. They all have benefits, and they all have shortcomings. What’s best for you depends on recommendations from your medical provider, your current level of conditioning, and your exercise goals. To inform your choice, let’s dig a little deeper into the notion of exercise intensity, how we quantify “high,” “moderate,” or “low intensity,” and what each has to offer.

Exercise Intensity Is Relative, Not Absolute

What feels intense to one person may feel easier to another, and vice versa. How you experience exercise depends on your current fitness level and history with a certain type of training. Let’s say, Amanda has been jogging and cycling consistently for 10 years and has even competed successfully in several 5K races (3.2 miles). Compare that to Kim, who walks her dog twice a day for exercise. From that comparison, we can safely assume that Amanda and Kim would experience the same cardiovascular workout very differently. We can conclude this because intensity is often determined as a percentage of your maximum heart rate (MHR) per minute and is influenced by factors like conditioning and prior experience.

For cardiovascular exercise, intensity is calculated based on MHR per minute in three percentage tiers. In low-intensity training, your heart rate is around 40% to 60% of your maximum heart rate. Moderate-intensity exercise ranges from 60% to 80% of MHR, and high-intensity exercise boosts your heart rate to 80% to 90% of your max. Unless you’re an elite athlete training for a competition, there’s no reason to exceed 90% of your MHR.

Maximum heart rate is determined by subtracting your age from 220. Let’s return to the example of Amanda and Kim. Although they have different fitness levels, they’re both 40 years old and, therefore, they’d have the same maximum heart rate of 180 beats per minute or bpm (220 – 40 = 180). However, with Amanda’s greater level of experience and conditioning, she would be able to perform a higher-level workout than Kim to reach the same training heart rate target of 80%. On the other hand, given Kim’s lack of experience and training, her heart rate would rise to a low-intensity training level of 40% of her max with a much easier workout. In short, as your level of experience and conditioning with a given type of exercise increases, the difficulty of the workout you’re able to perform at a given heart rate intensity level also increases. So, what Amanda could do at her training heart rate of 50% would greatly exceed that which Kim could do at her training rate of 50%. It’s the same relative 50% intensity, but the workout difficulty level would be very different between the two people. To determine your target training heart rate, select the training percentage you’re striving for and multiply that by your max heart rate. So, for both Amanda and Kim, a moderate-intensity training heart rate of 70% would be 126 bpm (180 x .70 = 126).

Determining intensity in resistance training is more nuanced as your heart rate will likely rise during exertion sets and fall during rest periods between sets. Therefore, your heart rate is not as steady as it is in cardiovascular training. Some experts suggest using the percentage of your maximal effort on a given set to measure intensity. For example, what is the maximum weight you can squat for 10 repetitions? Once you determine that answer (with safeguards in place like a safety rack or spotters), you could take 40% to 60% of that number for low-intensity training, 60% to 80% for moderate intensity, and 80% to 90% of that number for high-intensity training. However, other factors, such as the training velocity (or how fast you raise or lower resistance like a barbell, dumbbell, or band), also affect how much resistance you can tolerate. Furthermore, as you get stronger over time, those numbers will change. Given those variations, a better choice for the average exerciser to gauge resistance training intensity is “perceived exertion,” that is, a subjective measure of how hard exercise feels to you while you’re doing it.

The Borg Scale of ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) has been used for several decades in exercise science. Gunnar Borg’s original research in developing the scale showed a reasonable correlation between perceived ratings and actual physiological measurements such as heart rate and breathlessness.1

Nathan Coles, D.C., owner of Coles Chiropractic in New Bern, NC, and instructor for Trinity’s Certified Holistic Fitness Specialist program, says that an updated version of the original Borg scale is Trinity’s RPE of choice. The Revised Borg RPE scale ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 means “rest” and 10 means “maximal exertion.”

In a generally healthy person, low intensity would correlate to 1 – 2 on the Borg scale. Moderate intensity would be represented by 3 – 4, whereas high intensity would be achieved with a rating of 5 – 8. Avoid going above an RPE rating of 8 for training goals short of elite or Olympic athletes. Some people choose to use RPE for all types of exercise to make it simple, and unless you need to be more precise for your training goals, that’s perfectly fine.

Some Physiological Effects of Exercise Intensity

Now that we’ve defined different levels of exercise intensity, let’s look at how they affect your physiology. All exercise burns calories and offers many physiological benefits. However, if the goal is to burn a lot of calories in a short amount of time, then high-intensity exercise delivers, Coles explains. Yet none of us can maintain a sustained intense effort for very long. Lowering the intensity will generally enable you to persist longer, so at the conclusion of your training session, it’s possible to expend the same number of calories with low-intensity or moderate-intensity training as with high, or maybe even more with longer durations.

To gain the benefits of high-intensity training for a longer time, try “interval” training. Simply put, intervals are periods of intense effort alternating with periods of lesser effort. For example, in the popular high-intensity interval training method (HIIT), you would push into high-intensity training for one to two minutes and then drop down into moderate or low-intensity effort for one to two minutes, continuing to alternate those intervals of effort for the duration of your workout. You can make the intervals whatever length of time you wish. “Since it’s impossible for anyone to sustain a high-intensity level, HIIT is really the only option for a prolonged intense effort,” explains Coles.

Calories burned is one benefit of exercise, but another consideration is the fuel source of those calories – sugar or fat. High-intensity exercise burns more calories per minute, but those calories come from blood sugar (glucose) or muscle glycogen (stored glucose), whereas lower-intensity training uses more calories from fat, Coles explains. “Total fat burning depends on how long and how hard you exercise, as well as your fitness level and metabolism,” he says. Yet another consideration is this: high-intensity exercise helps build and maintain lean muscle and boosts your calorie burn even after you finish exercising. This “after-burn” effect is called “excess post-exercise oxygen consumption or EPOC,” says Coles. “And high-intensity exercise is the best way to trigger EPOC.” So, what’s the best intensity for long-term fat loss? Coles suggests combining different intensities in your routine. This way, you can reap the benefits of all levels of intensity.

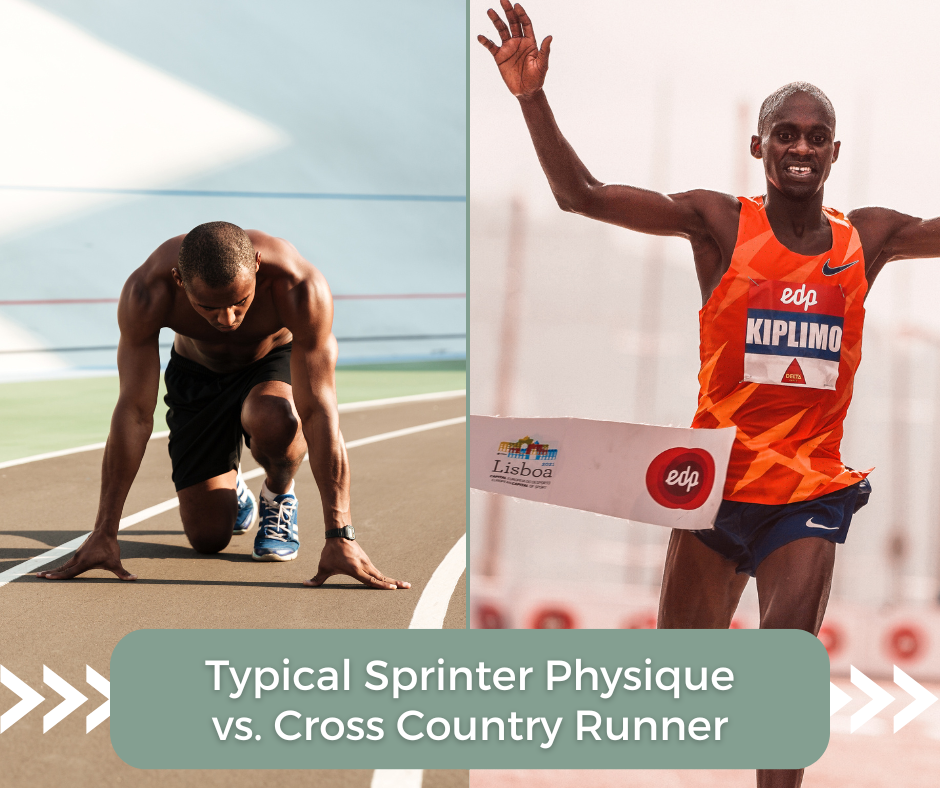

As stated above, high intensity builds more muscle than lower-intensity training. Think about the musculature of a sprinter versus that of a distance runner.

It’s clear that the explosive, high-intensity efforts of the sprinter stimulate more muscle hypertrophy (growth) than that of the longer duration, lower-intensity efforts of the distance runner (even though elite distance runners maintain an intensity that would feel high to most folks!). The longer duration of the lower-intensity training may also break down muscle tissue over time. Stimulating growth is a fine line to walk as it requires forcefully contracting muscle to stimulate hypertrophy, but then a period of rest is also necessary to repair and rebuild muscle fibers. While exercise is the impetus for growth, the actual growth process happens during rest, not during the workout.

The mechanism behind superior muscle hypertrophy in high-intensity training is the greater force of muscle contraction. Coles explains these powerful contractions result in “microdamage” of muscle fibers that, in turn, stimulate a process called “muscle protein synthesis,” whereby muscle fibers are repaired and restored, making them bigger and stronger. High-intensity training also triggers a hormonal response that increases the production of growth hormone and testosterone, which both support muscle growth, he says. Proper nutrition, e.g., adequate protein, also affects muscle hypertrophy, but that’s a discussion for another time. Lower-intensity exercise, he explains, doesn’t challenge your muscles as intensely or result in as much protein synthesis or as great of a hormonal response, making it less effective for building muscle mass. Don’t write it off, though! Lower-intensity training still improves your muscular and cardiovascular endurance, blood flow, blood-sugar balance, and fat-burning.

Here’s another note on the physiology of high-intensity training. Science is showing that HIIT increases the size and number of mitochondria, a.k.a. “the powerhouse” of the cell, Coles says. He explains that the mitochondria are the parts of our cells that convert the sugars, fats, and proteins we eat into usable energy, so making them more robust and increasing their number has many downstream physiological benefits, such as improved muscular metabolism and the ability to make more energy for all our body’s functions. Even cardiac rehab facilities have integrated HIIT training into their programs due to its strengthening effects on the cardiovascular system, including improving maximal aerobic capacity and cardiac contractility.

So, let’s take that physiology as well as a few practical considerations and examine some benefits and shortcomings of each exercise intensity level. Remember, there are many advantages to any exercise, as we discussed at the beginning of this article. The specific intensity you choose depends on your current physical condition and your goals.

Pros and Cons of Low-Intensity Exercise (40% – 60% MHR or 1 – 2 on the Revised Borg RPE)

Low-Intensity Pros

· Easier to start and maintain

· Uses more fat as the fuel source

· Recovery is quicker, so it can be performed more frequently

· Least risk of injury, so it may be a better starting place for beginners

· Less painful at the time and less muscle soreness later

· Lays the foundation for more intense exercise in the future

· Burns calories

· Builds endurance/stamina and increases blood flow as it activates your aerobic (oxygen utilization) system

Low-Intensity Cons

· Less muscle stimulation, so little if any hypertrophy, and even a risk of muscle depletion with long durations and not enough rest and recovery

· Generally, longer workouts as it takes more time to accomplish a similar workload as in moderate or high-intensity training

· Some physiological benefits for the cardiovascular system, blood sugar balance, muscular endurance, and brain health, but to a lesser extent than higher intensities

Pros and Cons of Moderate Intensity Exercise (60% – 80% MHR or 3 – 4 on the Revised Borg RPE)

Moderate-Intensity Pros

· Burns more calories per minute than low-intensity exercise

· Begins to burn calories from all fuel sources, including fat, glucose, and muscle glycogen, which can translate to greater long-term fat loss

· Greater stimulation of protein synthesis than low intensity, so some muscle hypertrophy and strength improvements

· Workouts can be shorter than low intensity as less time is required to reap physiological exercise rewards as intensity increases

· Individual variation precludes a definition of precise physiological benefits in the moderate or gray area of intensity. Coles notes that the best way to think about moderate exercise is this: It strikes a balance between the benefits of high and low-intensity training since, during moderate exercise, it’s likely that you’ll approach the boundaries of both.

Moderate-Intensity Cons

· More effort, which means potentially more discomfort and greater risk for injury than low-intensity training

· More recovery time required than low-intensity

Pros and Cons of High-Intensity Exercise (80% – 90% MHR or 5 – 8 on the Revised Borg RPE)

HIIT Pros

· Greatest muscle, strength, and metabolism increases

· Greatest increase in mitochondrial health and energy metabolism

· Most calories burned per minute and more burned after exercise is complete

· Stimulates muscle growth factors like growth hormone and testosterone

· Shorter workouts

· Heightened physiological effects on the cardiovascular system, blood-sugar balance, and brain health (The effects of exercise on brain health could be an entire article by itself, but here it’s enough to say that regular exercise enhances your brain’s ability to adapt and change, which, in turn, improves things like learning, memory, and acquiring new skills. HIIT appears to be especially helpful in this regard.)

HIIT Cons

· Higher risk for injury, muscle soreness, and overtraining

· Not a good starting place for rehabilitation or beginners (but can be integrated over time)

· Not sustainable for as long per session nor sustainable several times per week unless you’re highly conditioned

· Greater time needed for recovery

While any regular exercise holistically improves your health, you can see that as the intensity level changes, so do some effects on the body. For example, if your primary goal is general conditioning and fat loss, then low to moderate-intensity exercise is a good choice. If your primary goal is gaining muscle and strength or increasing the limits of your cardiovascular capacity, then high-intensity training is the best option.

Putting It All Together

Coles says the bottom line is this: since all exercise intensities offer special benefits, mix it up and try it all! Novice exercisers or those recovering from an injury or illness should check with their medical provider before beginning an exercise program. Once you have a green light, start slowly with low to moderate intensity to minimize the risk of injury and muscle soreness. But after a few weeks of mastering the movements and acclimating your body to the effort, dip your toe into the higher intensity levels occasionally to see what happens. If all goes well, keep things interesting and consider creating a routine that cycles through different intensity levels, always remembering to give yourself enough time for rest and recovery. Pro tip: incorporate a few minutes of warm-up at the beginning and cool-down/stretching at the end of your cardio or resistance workouts.

With more experience and as your fitness level improves, you can add more high-intensity workouts if you desire. Listen to your body and make the days of the week work for your life demands and schedule. Activity recommendations from the Department of Health and Human Services3 are 150 minutes of moderate activity per week or around 30 minutes, 5 days per week. But, since we know that about 80% of Americans are insufficiently active4, the main objective is to work some movement into your life. Wouldn’t it be amazing, though, to reap the benefits of all the different levels of exercise intensity? You can do it with proper planning and consistent effort.

To learn more about the benefits of an active lifestyle, check out the Certified Holistic Fitness Specialist program or call a Trinity Enrollment Specialist at 800-428-0408, option 2.

References

1. n.a. (n.d.). Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion. Physiopedia. Downloaded 1/30/2024, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Borg_Rating_Of_Perceived_Exertion.

2. n.a. (2017). Benefits of Exercise. MedLinePlus, National Library of Medicine. Downloaded 1/20/2024, https://medlineplus.gov/benefitsofexercise.html.

3. n.a. (June 2, 2022). How Much Physical Activity Do Adults Need? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Downloaded 2/1/2024, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm#:~:text=Each%20week%20adults%20need%20150%20minutes%20of%20moderate-intensity,to%20the%20current%20Physical%20Activity%20Guidelines%20for%20Americans.

4. Piercy, K.L., et al. (2018). The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Journal of the American Medical Association, 320 (19): 2020 – 2028. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854 .